Encryption Fundamentals

Overview

We often have this idea that obscuring our systems isn't a legitimate way to make things secure, for good reasons. However, sometimes we must transmit messages in ways that are easily intercepted. People have struggled with this

problem for millennia and have developed many different methods for secure communication; most of them involve obscuring the real content of our message behind a wall of jumbled information that can only be understood with the correct key. This is the inherent nature of encryption - a vast and complex world of ciphers and protocols, sniffers and code breakers. The war-time needs to break encryption during World War II and the Cold War are in many ways

responsible for the development of the modern computer in the late 20th century. Many of the visionary precursors of the modern computer were instrumental in creating improvements to encryption, often by breaking existing ciphers.

So how do we encrypt things in a manner that provides some certainty that no one can decrypt them without our key? This is difficult to explain, so we're going to start with the oldest and simplest types of ciphers and begin working our way up to more modern techniques.

Monoalphabetic ciphers

The oldest ciphers in the world are simple monoalphabetic ciphers. You've probably seen them in the newspaper, or in puzzle books where you're asked to decipher a famous saying or phrase. In a monoalphabetic cipher, each letter is replaced by a different letter to scramble the plain text.

Perhaps the most well-known monoalphabetic cipher is the Caesar cipher, which replaces every letter with whatever letter comes three places later. This cipher was developed for the Roman alphabet, but it can be used for nearly any alphabet.

Caesar Cipher Key

Plain-text ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

Cipher-text defghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzabc

Take, for example, this plain-text encrypted with the Caesar cipher:

The TCP/IP suite makes use of five different layers to get its job done.

Wkh WFS/LS vxlwh pdnhv xvh ri ilyh gliihuhqw odbhuv wr jhw lwv mre grqh.

But monoalphabetic ciphers don't have to be sequential. You could use any key.

Sample Monoaplhabetic Key

Plain-text ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

Cipher-text jiuasydfnpcmqwkhztolvbgxer

Monoalphabetic ciphers were first used shortly after the invention of writing and continued to be used for secrecy until the late 19th century. This was the strongest encryption available until the invention of the polyalphabetic cipher in the mid-16th century. Defeating monoalphabetic ciphers is rather trivial, but for many centuries, there was nothing better. People simply had to rely on a combination of non-obvious keys, serendipity, and a reasonably secure transmission media in order to communicate privately.

Attacking a monoalphabetic cipher is simply a process of frequency analysis. Assuming that you know which language the plain-text is written in, you can make educated guesses at the plain-text based on the frequency that each letter of the cipher-text appears. For example, in English the most common letters are e, t, a, o, i, and n. The least common are q, x, j, k, v, and b. Assuming the letters q, w e r t, and y appear most often in the cipher-text, we can assume that these probably indicate several of the most common letters in the plain-text. Similarly, if a, s, d, f, g, and h are the least common letters, there's a strong chance that they indicate one or more of the least common letters in the English language.

This can be combined even further with letter groupings. For example, the letter q is almost always followed by u in English. By applying frequency analysis, we can determine a goodly portion of the key, then make educated guesses at the plain-text to learn more of it until the message is deciphered.

If you want to try your hand at breaking a monoalphabetic cipher, have fun deciphering this cipher-text. It's a simple randomly generated monoalphabetic key on a portion of a "well-known" plain text. Traditionally, all punctuation is removed, and I have chosen to follow tradition.

QMTDSRTAUSQFDCITABZSKAQFCEJSXVDSEJQBQFMTYMIQBECDDCITAQMBQDCITAESZQBQFQSX

VCQBECDDICZIYMIQBECDYCAFSXISKAZTFRSAJSMIQBECDBQCVBFSXCUBQZSUTAFMSKOMCQBF

BZEDKNTQZSZYMIQBECDFACZQUBQQBSZUTNBCQKEMCQDBOMFSAACNBSQBOZCDQVCQBECDDICZ

IFMBZOFMCFBQECYCVDTSXCEFKCDDIFACZQUBFFBZONCFCBQYCAFSXFMTYMIQBECDDCITAQMB

QBZEDKNTQZTFRSAJECANQESYYTARBATQXBVTASYFBEECVDTACNBSRCHTQCZNTHTZBZXACATN

DBOMFQMTYMIQBECDDCITAFKAZQFMTNBOBFCDYCEJTFBZFSQSUTXSAUSXCZCSDOKTQBOZCDFM

CFECZVTFACZQUBFFTNFSCZSFMTAZSNTSZFMTZTFRSAJ

Vigenere and his square

During the Middle Ages, Europeans realized that the monoalphabetic cipher was simply too weak and that a better solution needed to be found. Prior to this, other cultures had already learned of the monoalphabetic cipher's weakness, though improvements were few and far between.

Polyalphabetic ciphers were first described in the mid 16th century by Giovan Battista Bellaso, but have been "rediscovered" several times over the years and are often misattributed to Blaise de Vigenere. Bellaso had the idea of using two monoalphabetic ciphers and alternating between them at every letter to produce a stronger cipher. Today, most polyalphabetic ciphers are known as Vigenere ciphers.

Polyalphabetic ciphers use several different alphabetic shifts throughout the plain-text to create the cipher text. Each letter of the key suggests a different alphabetic shift to use, and those shifts are typically looked up on a table called a Vigenere Square. The key is repeated until it matches the length of the plain-text to be encrypted, and the cipher text is derived from the key and the table below.

Vigenere Square

+------------------------------------------------------

| - A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

| A a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

| B b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a

| C c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b

| D d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c

| E e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d

| F f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e

| G g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f

| H h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g

| I i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h

| J j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i

| K k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j

| L l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k

| M m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l

| N n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m

| O o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n

| P p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o

| Q q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p

| R r s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q

| S s t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r

| T t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s

| U u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t

| V v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u

| W w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v

| X x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w

| Y y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x

| Z z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y

+------------------------------------------------------

When you encipher a plain-text with the Vigenere Square, you must choose a key which can be a word of any length or simply some random text of a given length. Let's encipher the following plain-text using the key SLACKWARE.

At first glance, switches are indistinguishable from hubs.

Plain-text ATFIRSTGLANCESWITCHESAREINDISTINGUISHABLEFROMHUBS

Key SLACKWARESLACKWARESLACKWARESLACKWARESLACKWARESLAC

Cipher-text SEFKBOTXPSYCCMWICGZPSCBAIEHADTKXCUAWALBNOBRFQZFBU

As you can see, this is much stronger than a monoalphabetic cipher because each letter in the plain-text can be translated to multiple letters in the cipher-text. In fact, this form of encryption is so much stronger than a

mono-alphabetical cipher that it was originally dubbed indecipherable. As we'll see soon, that is only partially right.

Attacking a Vigenere cipher uses the same basic tactics that are effective on the monoalphabetic cipher, predominately frequency analysis, but with a twist. The first step in breaking the Vigenere cipher is determining the length of the key. This can be done by sheer guess work, or by looking for commonly repeated chains of letters in the cipher text. Let's presume that the following text is our plain-text:

Internet Control Message Protocol, or ICMP for short, is mostly used to

transmit error messages between machines. For example, if a router

can't seem to find a node you're attempting to communicate with, you

may see an "ICMP Destination Unreachable" error message. ICMP is used

to transmit the most basic of information between nodes, and is highly

specialized to this task to the point that it cannot carry arbitrary

data in the way that TCP or UDP can (more on these later). Each ICMP

packet is given a certain "type" that specifies its use. Certain types

may have a (sometimes optional) data section that can carry some small

amount of arbitrary data.

In this plain-text, several words are used multiple times, particularly the words "ICMP", "the", "data", and "message". I'm going to encrypt it with a key of a certain length, and then we're going to determine what that key is using some basic math and a variation on the frequency analysis done in breaking the monoalphabetic cipher.

AYTGBJEKGGYTTYHMVWKLGGZNOKSUZLQBECDTXZRURKRKMKXOUDHYLWWOTQDNAEWETTGBNOIQ

WDSCQASSILHEGXIATLAYEUPKRVBSXPNOEFRVGFTGBYAEXKPEODKFZRVLNQNAYFYJPAVDAMGX

AYGVYYODQMYIEKPENMLSYQEIAPWWPAPSYMGHWDTKXWTZSFFNTOWCYETWEGBNOIQWDSCQAITQ

HTSWCADKSLCAPCIIKXZPMQCPBRWANOHSJFFVELTKYJBVXOPEPXKDVWSYDKCDIXLDJSROYIRP

AKEFDKTYMKEAUUPOKLWAOKXPTYELTTEKJNFXULRTIWRSMLCATIZAKEAYTJOSAPXZLTVMLOIY

VACCXIOIIGYTJOOECELPRGKYHZGEAPCMGEKMKRIXOJATIJEAKXPYGILSAVCLETMXTEUSPSLW

WNETDWIEXQAEUWWYYENPAUYIEKMEPSQZPIFRSWDCDWSVGLTOPDDAKGSYCCBNYJSEPSOKHLRQ

GFNVYBAIFAERCBUDRXS

This cipher text is short, making analysis difficult, but by looking for common two and three-letter combinations we find a few that stand out quickly and note their positions in the cipher text.

GYT : 10 370

MK : 45 297 396

LCA : 226 334

This simple operation gives us an opportunity to guess at the key length by finding the difference in their positions and factoring them.

GYT : 370 - 10 = 360

MK : 396 - 297 = 99

MK : 297 - 45 = 252

LCA : 334 - 226 = 108

Now we just find all the possible factors.

360 : 2 * 2 * 2 * 3 * 3 * 5

99 : 3 * 3 * 11

252 : 2 * 2 * 3 * 3 * 7

108 : 2 * 2 * 3 * 3 * 3

There are two factors that stand out as particularly common here: 2 and 3. So, we'll assume that the key length is a multiple of 2 or 3 in some combination, for example 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, and so on) We can determine that the key length is not 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, or 12, because none of those numbers are a factor of 99, so the only choices left to us are 3 and 9 (11 is ruled out because it is not a factor of 360, 252, or 108). For now, we're going to guess that the key is 9 characters long, but we still have no idea exactly what those characters are. We'll figure that out by applying frequency analysis on the cipher-text after we've counted each occurrence of each letter according to our assumed key length.

Counting the first letter, and every ninth letter thereafter (1, 10, 19, 28, and so on), we get the following frequency of letters. Based on this frequency, we can make a guess at the particular alphabetic shift in use by comparing the

frequency of the letters in the cipher text to their counterparts in the alphabet.

CIPHER-TEXT FREQUENCY PLAIN-TEXT GUESS

A 6 I

B 0 J

C 0 K

D 1 L

E 5 M

F 1 N

G 4 O

H 1 P

I 0 Q

J 2 R

K 5 S

L 8 T

M 1 U

N 1 V

O 1 W

P 0 X

Q 1 Y

R 0 Z

S 5 A

T 1 B

U 2 C

V 2 D

W 7 E

X 2 F

Y 0 G

Z 2 H

This particular shift was chosen because it lines up the most frequently occurring letters in the English language with the most frequently occurring letters in the cipher-text. This just happens to be the "S" shift in the Vigenere Cipher. If we continue this strategy, we'll soon come to the conclusion that the key is "SLACKWARE". The plain-text follows:

INTERNETCONTROLMESSAGEPROTOCOLORICMPFORSHORTISMOSTLYUSEDTOTRANSMITERRORM

ESSAGESBETWEENMACHINESFOREXAMPLEIFAROUTERCANTSEEMTOFINDANODEYOUREATTEMPT

INGTOCOMMUNICATEWITHYOUMAYSEEANICMPDESTINATIONUNREACHABLEERRORMESSAGEICM

PISUSEDTOTRANSMITTHEMOSTBASICOFINFORMATIONBETWEENNODESANDISHIGHLYSPECIAL

IZEDTOTHISTASKTOTHEPOINTTHATITCANNOTCARRYARBITRARYDATAINTHEWAYTHATTCPORU

DPCANMOREONTHESELATEREACHICMPPACKETISGIVENACERTAINTYPETHATSPECIFIESITSUS

ECERTAINTYPESMAYHAVEASOMETIMESOPTIONALDATASECTIONTHATCANCARRYSOMESMALLAM

OUNTOFARBITRARYDATA

Unbreakable - the one-time pad

If you step back and look at what we just did, you may come to the conclusion that breaking the Vigenere Cipher becomes much more difficult as the key increases in size and complexity. You'd be right! If the key is as long as the

text that is being enciphered, we cannot employ frequency analysis in the same way that we did above because the key never repeats. So what happens if the key is at least as long as the cipher-text, and the key is randomly generated so it cannot be guessed? And what if you never re-use the key? Then, you're using a cipher that cannot be broken.

The one-time pad is a special version of the Vigenere cipher which accomplishes what no other known cipher possibly can - guaranteed cipher-text security. This was mathematically proven many years ago, and subsequent tests have confirmed it. The strength of the one-time pad lies in several facts. First, since the key is at least as long as the plain-text, it never repeats, so pattern analysis techniques cannot be applied on repeating sections of the cipher-text. Second, since the key is randomly generated, correctly guessing one portion of the key tells the attacker nothing about other portions. In mathematical terms, every possible combination that generates a meaningful plain-text is no more likely to be correct than any other. This means that "attack the hill at dawn" is just as likely to be correct as "defend the nearby town".

So why don't we use one-time pads everywhere?

The one-time pad is what's known as a symmetric cipher - meaning that the same key must be used to both encrypt and decrypt the message. This means that both parties must share the same key. Distributing these keys can be extremely difficult, because anyone who intercepts the key can decrypt the message. Furthermore, each key can only be used to encrypt a single message. Re-using a key for multiple messages presents an attack opportunity by comparing the encrypted messages. An attacker can make guesses at one cipher-text and then apply that portion of the key to other texts to see if his guess is correct. Once any portion of the key is known for certain, it can be used to decrypt the corresponding portion of all cipher-texts using it. This often lets the attacker make educated guesses about adjacent portions of the key until the entire key is known.

Additionally, the key must be completely random and at least as long as the data you wish to encrypt. This means that encrypting a web page or an image (let alone a database or a novel) requires an enormous key. Computers are not good at generating truly random events - the basic principles of a computer are such that a given input should always produce the same output. There are some methods by which computers can create random or pseudo-random numbers, but they are computationally expensive and often require time to generate a key of suitable length. Imagine generating new one-time pad keys for every page load on an HTTPS site and you can easily see how this would bring a server to its knees.

In modern history, the one-time pad was frequently used by spies on both sides of the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. The CIA and KGB had to provide a steady stream of random keys to their spies, typically via dead drops. A major portion

of counter-spy activities by both sides involved locating these dead drops and either destroying the keys or copying them. The value of intercepted keys was strictly limited however, if a single key was only ever used to encrypt a single

text.

Secret words

Not an actual part of cryptography, secret words have existed since time immemorial. These allow two parties to embed a hidden meaning into their correspondence in such a way that no other party who might read or hear the conversation would understand. We won't go into great detail here as they're not applicable to ciphers and keys, but are simply too fascinating to go unacknowledged.

When two parties communicate using secret words, they must have first agreed that certain words or phrases have a special unrelated meaning. For example, the word "truck" might mean "rendezvous with me at midnight" and "hamburger" might mean "under the Flint River bridge". So if two lovers were having an affair (or just wanted to go fishing), one might say to the other, "We stopped at McDonald's for hamburgers and I spilled the drinks all over the inside of my truck." The other person would then know to meet their lover (or fishing partner) at midnight under the Flint River bridge.

Secret words need not even be words. In fact, the most common everyday use of secret "words" comes from the humble first base coach who informs the batter to swing away, bunt, take a pitch, or hit and run with a flurry of hand gestures, only a few of which have any real meaning. Quarterbacks calling audibles also use secret words to obfuscate their plays from the opposing team.

Other more sinister modern examples involve secret words in Youtube videos, which many people believe include hidden messages for terrorist agents operating independently of one another. Other examples are found in the jargon of various

underworld groups like gangs who use their own combination of slang and inflection to convey information that isn't obvious to the uninitiated person who might overhear their conversation.

Hash functions

Hash functions are often called "one way hashes" and aren't true encryption ciphers. Rather, they produce a message digest - a small message that can be used to verify data integrity. They do sometimes behave a bit like encryption

ciphers, and are often included as part of an encryption protocol. The most common hash functions are MD5, SHA1, and SHA2, but others exist.

Hash functions operate by taking chunks out of a file and processing them mathematically to determine a result. Hash functions always output their results in a fixed-length. For example, MD5 outputs a 128-bit hash and SHA1 outputs a 160-bit hash. It's important to note that hash functions are an example of many-to-one output. In other words, two entirely different files can produce the same output. For this reason, it's impossible to reverse the hash. In other words, you cannot hash a message, send the resulting hash to a colleague, and expect to college to "unhash" it to get the original input. Even if it were possible to "unhash" a message, there are an infinite number of possible matching inputs so your colleague would have no way of being certain which one to use.

Hashes are typically used to determine that a message or file has not been corrupted or altered in transit. For example, if you know the MD5 hash for a large file (often published alongside the files on an FTP server), you can process the file after downloading it to make sure it was not altered during transit. Changing even a single bit within a file often changes at least half of the hash, so it becomes readily apparent that something isn't right.

Hash functions are rated for security based on the difficulty of determining a collision. For example, MD5 and SHA1 are no longer considered strong enough for use as attacks have proven that it's feasible for an attacker to find or create a collision. Since hash functions are many-to-one, an attacker could generate a harmful file that produces the same hash as a helpful file.1

Because there's no way to reverse a hash, you might think that they are largely useless for encryption, and you'd be correct. What they are incredibly useful for, however, is verification. Encryption hashes are a big part of asymmetric encryption verification, which we'll discuss in more depth in the Asymmetric ciphers section.

Symmetric key ciphers

When Charles Babbage and others used mathematics to demonstrably break the Vigenere cipher, people began experimenting with new ciphers based not on language, but on arithmetic. These tests resulted in many famous ciphers such as the Enigma Machine of World War II, but really took off when computers became capable of performing large arithmetic operations with speed and precision in the 20th century. There are a great many symmetric ciphers, so we won't discuss them all. Additionally, due to their complexity, we won't go into formal detail of how they work as we did with alphabetic ciphers. Instead, I'll include references to online articles that describe how these ciphers work in exhausting detail.

Perhaps the most well-understood of all symmetric ciphers is Data Encryption Standard (DES), and its close cousin, 3DES, but it's no longer considered cryptographically strong. Most symmetric encryption today is handled by Rjindael, or Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Other popular symmetric ciphers are Blowfish, Twofish, RC4, and IDEA. Of these, AES and Twofish are the strongest. The vast majority of encrypted Internet traffic today utilizes symmetric keys and the AES cipher.

Symmetric key ciphers suffer from one universal and enormous limitation - the same key used to encipher the data must be used to decipher it as well. This means that a secure key exchange of some kind must be performed for both parties

to communicate securely. This requirement prevents symmetric key ciphers from being the sole method used to encipher data on the Internet. We'll discuss more about how this limitation is worked around when we get into a detailed discussion of TLS/SSL.

DES and 3DES

We're going to begin our discussion of symmetric key ciphers with DES 2. This is no longer considered cryptographically strong due both to its short key-size and short block-size. When DES was adopted in 1977, a key length of only 56 bits was sufficient to secure communications for just about anyone. Estimates from prominent cryptanalysts of the day proposed that it would take $20 million dollars (in 1977 money) to build a computer capable of

brute-forcing DES in a reasonable time frame. This meant that well-funded organizations like the NSA and the KGB could feasibly break DES even when it was adopted, but corporate competitors and even large hacker groups found breaking

it unfeasible. Fast-forward nearly 40 years and the bare minimum we consider for security is a 128-bit key length, which has 4,722,366,482,869,645,213,696 times as many possible permutations, and DES has been brute-forced many times in short time frames by even small non-profit organizations.

DES also uses a 64-bit block size, which is considered on the small end of the spectrum today but is not nearly as big a deterrent against its use as its tiny key size. DES is a block cipher, meaning it breaks up the data to be enciphered into 64 bit blocks (as mentioned above). Each block is then split into two 32-bit blocks and operations, or rounds, are alternatively performed upon each block. In each round, a portion of the 56-bit key is used to alter or not alter individual bits, and each bit can end up being altered numerous times, not just from the round, but also from a XOR operation performed afterwards. Each round produces a new 32-bit piece, and this new piece is XORed against the other (which was not modified by the round). This provides a layer of protection which s not easily broken.

Deciphering a DES-protected cipher-text is a simple process of using the key to reverse the steps. Other ciphers often require a different method for enciphering and deciphering, but this ability to simply reverse operations was a huge selling point for DES when it was adopted, as the same expensive and specialized hardware could be used for both operations. In the 1970s and well into even the 21st century, encryption operations required specialized hardware to be performed in a timely manner. Software implementations running on standard processors of the time were insufficient for the task.

It's important to note that no attacks other than brute force have been proven to work against DES in anything but a theoretical state. Given that, a few smart people determined that they could easily triple the key size of DES. These implementations are termed Triple DES, or 3DES for short. 3DES utilizes a 168-bit key (in reality, three different 56-bit keys), and performs the exact same operations as DES with a twist. The first key is used to encrypt the data normally. The second key is then used to decrypt the data. Since this key is different from the first, it produces gibberish. The third key is then used to encrypt this gibberish to produce even more gibberish. Deciphering 3DES performs these steps in the opposite order. The third key deciphers the text, the second key enciphers it, and the first key deciphers that to produce the original plain-text. In theory, DES could be extended further into 5DES or 7DES, but the law of diminishing returns rears its ugly head. A 64-bit block size is too small today regardless of the key size, and DES operations are much more computationally expensive than more modern methods anyhow.

AES and Rjindael

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)3 is the successor to DES. You'll sometimes see this referred to as Rjindael. Rjindael was the original name of the cipher (actually a suite of ciphers) that won the National Institute of Standards and Technology's (NIST) AES contest in the late 90s to develop and adopt a stronger cipher to replace DES. Since winning the contest and being formally adopted by most everyone, Rjindael was renamed AES. Like DES, AES is a block cipher, but it uses a 128-bit block size and key sizes of either 128-bit, 192-bit, or 256-bit. Since every bit doubles the size of the key or block, this represents an enormous leap in complexity over DES.

Unlike DES, AES eliminates the Feistel rounds and instead operates on the block within a 4x4 matrix. This allows a computer to calculate the AES cipher quickly whether the operation is performed in software or in dedicated hardware. Indeed, a major selling point of AES that promoted its adoption as an NIST standard was its performance on embedded devices with limited capabilities and no specialized hardware.

AES has been studied extensively over the last fifteen years. During that time, many different attempts to break it have been attempted. No known attacks are yet feasible. Indeed, the current best attacks against AES will require billions

of years to complete (on current hardware) and require that the attacker possess more data encrypted with the same AES key than currently exists on all the computers in the world combined. Properly designed cryptography works.

Asymmetric ciphers

For the majority of human history, encryption and decryption have always been performed using the same key. This presented an enormous problem - how do we give our recipient the key without the possibility of its interception by a

third party? Imagine for a moment that to shop online with Amazon, you must first exchange a key with them. How do you do this safely? You cannot encrypt the key and send it to Amazon, as that would require you to exchange a second key instead. Amazon couldn't simply publish the key, because then anyone could use it to decrypt your credit card information when you placed an order. Every online retailer would be forced to generate unique keys for every customer and somehow distribute those keys in a secure manner.

This problem plagued mankind as often the easiest way to break some one's encryption was to simply steal their encryption key while it was enroute to its destination. During times of war, intercepting the enemy's encryption keys was a major victory. Researchers had tried and failed many times to produce a cipher that didn't require the recipient to know the key used to encrypt the data in order to decrypt it. Also, many people believed that mathematics, being wholly deterministic, could not do such a thing.

Some knew this to be incorrect. In particular, the British government had developed asymmetric ciphers and kept the information hidden. Private researchers would later rediscover these secrets and make them public. For these private researchers, there was a tantalizing analogue of how this could be done in real life. Imagine for a moment that Alice needs to correspond with Bob without the possibility that anyone else could steal their letters. To do this, Alice and Bob both buy different padlocks at different stores, both of which have two identical keys. Alice then places one of her keys into a box and seals it with her padlock. The box is mailed to Bob, who then puts his padlock on it and sends it back.

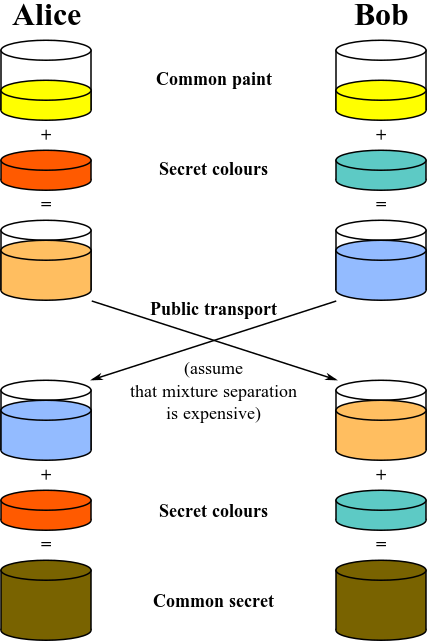

When Alice receives the box, it has both her padlock and Bob's on it. Within the box is the key to Alice's padlock. Now, Alice uses her spare key to remove her lock and mails the box back to Bob. When Bob receives it, he is able to remove his padlock and retrieve Alice's key within. They can then repeat this process with Bob's key so they can securely exchange information using either padlock (or both). Another analogue involves mixing paint colors. When two colors are mixed together, they form a third color. It's nearly impossible to separate this third paint color down to the original two colors, so color could, in theory, be used as an encryption key. Here's how.

Alice and Bob both publicly agree on a shared starting color. In this example, let's say it's yellow. At this point, anyone listening in knows that the starting color is yellow. Both Alice and Bob then randomly pick a color. In this example, Alice picks a shade of orange and Bob picks something like aquamarine. They each mix their secret color with yellow to produce two new colors. These colors are transmitted to one another. Since it is extremely difficult to separate the yellow from the mix, even if the colors are intercepted, an attacker will not know each person's randomly chosen color. Alice and Bob then add their secret color into the other person's mix to generate a new color (their shared private key). Here's an example illustration of this process provided by Wikipedia. 4

Diffie-Hellmann Key Exchange

In 1976 the world of cryptography was turned on its head when Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman introduced a mathematical way for two people to share a secret encryption key over an unsecured, public channel without exposing the key to any one who might be listening in on the conversation. Their technique used a branch of mathematics that is often ignored, but used every day - modular arithmetic. Also colloquially known as clock math, modular arithmetic is a

system of counting in which integers repeat or wrap around after reaching a certain maximum value. This is analogous to a clock where 1:00 directly follows 12:00. We would say that clocks are modulus 12 for this reason.

This is mathematically similar to the way that remainders were determined when doing division in grammar school, before we all learned about fractions. For instance: 13 / 4 = 3 with a remainder of 1. In modular arithmetic, we're only

interested in the remainder and the same equation is written this way: 13 mod 4 = 1.

Another key concept of modular arithmetic is the concept of "primitive roots".5. Primitive roots of a number "p" are determined by taking every power of that number less than "p" (a^1, a^2, a^3, ... a^p-1) and modulating that number against "p". If the results are the total set of integers from 1 to p-1, then "a" is a primitive root of "p". That's a lot to take in, so let's look at some examples. First we're going to start with "p" = 19 and find a primitive root. We do this by first choosing all the prime numbers less than 19, then raising each of them to every power between 1 and 18. Finally, we take that figure, divide by 19, and take the remainder.

Here's a quick python script that finds all the primitive roots of 19. You can modify the values of "modulus" and "primes" to check other numbers for primitive roots if you like.

Note: This requires Tabulate and was only tested in Python 2.7.

'''

Calculate the primitive roots of a given modulus. Program is

limited to small prime numbers due to the limits of long integers.

'''

from tabulate import tabulate

# Declare variables

modulus=19

primes=[2,3,5,7,11,13,17]

header=['Prime']

for i in range(1,modulus):

header.append(i)

roots=[]

# Compute and store the modulus for each prime to each power

i=0

for prime in primes:

roots.append([])

for x in range(1,modulus):

roots[i].append(prime**x%modulus)

i+=1

# Insert the first column's header

i=0

for entry in roots:

print primes[i]

entry.insert(0,primes[i])

i+=1

print tabulate(roots,headers=header)

And here's the output.

Prime 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

------- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ----

2 2 4 8 16 13 7 14 9 18 17 15 11 3 6 12 5 10 1

3 3 9 8 5 15 7 2 6 18 16 10 11 14 4 12 17 13 1

5 5 6 11 17 9 7 16 4 1 5 6 11 17 9 7 16 4 1

7 7 11 1 7 11 1 7 11 1 7 11 1 7 11 1 7 11 1

11 11 7 1 11 7 1 11 7 1 11 7 1 11 7 1 11 7 1

13 13 17 12 4 14 11 10 16 18 6 2 7 15 5 8 9 3 1

17 17 4 11 16 6 7 5 9 1 17 4 11 16 6 7 5 9 1

Looking at this, we can clearly see that 2, 3, and 13 are primitive roots of 19 because every integer from 1 to 18 appears exactly once in the list. No numbers are skipped or repeated.

The discrete logarithm problem

The discrete logarithm problem is what makes the Diffie-Hellmann key exchange work. Let's take a look at this using the modulus 19 and the primitive root 13. If we pick any number (let's say 10), finding the modulus is relatively easy.

Problem

--------------------

13**10 mod 19

Solution

--------------------

13**10 = 137,858,491,849

19 * 7,255,710,097 = 137,858,491,843

137,858,491,849 - 137,858,491,843 = 6

The reverse is not so easy. Logarithms are the reverse of exponents and allow us to solve certain problems like this example:

13**x = 137,858,491,849

In this situation, you would simply take the 13th log of 137,858,491,849 and you would get 10 as a result. But how do we solve this problem?

13**x mod 19 = 6

There is no formula that can calculate the value of "x" in this equation. Instead, we have to rely on brute force and try every possible value starting at "1" until we find a result. When the numbers are small like this, brute forcing it is easy. But what if the equation looks like this?

96,199,135,481,543,734,721**x mod 351,661,877,182,395,774,689,917,396,129,897,423,376 = 197

Do you want to brute force that equation? In this example, the numbers were only 20 and 40 digits long. What if they are hundreds or thousands of digits in length? Brute forcing such large numbers requires both an enormous expenditure

of money on super computers and an enormous expenditure in time. So how does the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange use the discrete logarithm function to exchange secrets?

Let's go back to our earlier example using the prime number 19 for the modulus. Alice and Bob want to talk to one another securely, so they need to exchange a key without Eve eavesdropping on them. They agree publicly to use the modulus 19 and its primitive root 13. Since this transfer is public, Eve is able to acquire that information.

Alice and Bob then each chose a random number and plug it into this equation for "x".

13**x mod 19

Let's say Alice chooses 12 and Bob chooses 8.

13**12 mod 19 = 7

13**8 mod 19 = 16

Alice knows that the first part of her private key is 12. Bob knows that the first part of his private key is 8. They now publicly share these answers with each other. Even if Eve intercepts this transmission, she only knows the modulus

19, the primitive root 13, and the answers 7 and 16. She's busy playing a sort of mathematical Jeopardy where she knows the answer but has to brute force the questions (12 and 8 in this case).

Now Alice and Bob perform another mathematical operation using the answers given to them and the first part of their private keys. Alice takes the answer she got from Bob (16) and raises it to the power of her privately chosen number (12).

Bob takes the answer he got from Alice (7) and raises it to the power of his privately chosen number (8). After taking the 19th modulus of both of these numbers, they arrive at the same secret key (11).

Alice

--------------------

16**12 mod 19 = 11

Bob

--------------------

7**8 mod 19 = 11

It's not clear at first, but both Alice and Bob performed the exact same mathematical operations - all without knowing one of the numbers they were using. Consider the example of Alice. She received the number 16 from Bob, which was derived as:

13**8 mod 19 = 16

So her calculation was really:

13**(12*8) mod 19 = 11

Similarly, Bob did the same operation. He received the answer 7, which was calculated as:

13**12 mod 19 = 7

So his operation was really:

13**(8*12) mod 18 = 11

Alice and Bob have just arrived at their secret key (11) without either one of them knowing the full equation! Since neither transmitted their secret piece of the equation, Eve is forced to throw up her hands in frustration.

Advantages and disadvantages of Diffie-Hellman

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange brings a few important advantages with it. First and foremost is its ability to guarantee Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS). We haven't discussed PFS, but it's an important requirement for certain communication channels. Since new keys are generated for every connection, even if an attacker manages to brute-force a key, that key is only valid for that single session. It cannot be used to decrypt past or future communications. In particular, government espionage departments have the ability to intercept and store vast amounts of encrypted data. Even if they do not currently know the encryption key used to generate the garbled text, they can store it indefinitely. If later, they learn the key via some means, they can retrieve that stored cipher-text and decrypt it. Diffie-Hellman is resistant to these

types of attacks because it constantly generates new keys.

One of the big disadvantages of Diffie-Hellman is the overhead it imposes. Since new keys have to be generated for every unique connection, this forces both parties to generate random numbers. Computers are not particularly good at

random number generation, so this can have the effect of greatly slowing down the initial connection.

RSA

Diffie-Hellmann proved to the world that it was possible to share a secret key securely between two people over an insecure channel, but the Diffie-Hellmann algorithm lacked certain requirements necessary for complete security. Notably, Diffie-Hellmann is only a key-exchange method for agreeing upon a shared secret key. Additionally, new keys must be constantly generated when using Diffie-Hellmann. What was really needed was a method we could use to both

encrypt and sign our communications. This signature piece is important, because it provides an identity guarantee. That means that Alice can cryptographically sign her communications to Bob in a way that Eve cannot replicate and works to

prevent man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks against cryptography.

To that end, a team of cryptographic researchers (Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman) worked together and discovered the RSA method of cryptography. RSA relies on the difficulty of factoring large numbers, specifically large numbers that are the

product of only two large prime numbers. To explain this difficulty, let's pick a relatively small number and factor it by hand. Doing this requires a certain amount of trial and error.

493

------------------------------

493 / 2 = 246.5

493 / 3 = 164.333333333

493 / 5 = 98.6

493 / 7 = 70.4285714286

493 / 9 = 54.7777777778

493 / 11 = 44.8181818182

493 / 13 = 37.9230769231

493 / 17 = 29

------------------------------

17 * 29 = 493

Given the numbers "17" and "29", it only requires 1 step to multiply them together to get "493". Given "493", it took us 8 steps of trial and error to determine which prime numbers would divide it evenly. Were we to use much larger numbers, the corresponding number of steps would increase exponentially. Naturally, computers are much faster at factoring numbers than humans are, but as the size of the number increases, the exponential increase in the difficulty quickly outpaces the computer's speed until it can take hundreds of years to perform the arithmetic. One of the key advantages to this sort of exponential increase in difficulty is that as computers get much faster, we only need to increase the size of our numbers slightly to keep pace.

The phi (or Φ) function

This is almost certainly something you've never heard of before, unless you're really into mathematics. Φ is the total number of integers that don't share a factor (other than "1") with a given integer. Let's look at an example using the number 18.

Φ 18 = ?

------------------------------

Fact(1) = [ ]

Fact(2) = [ 1, 2 ]

Fact(3) = [ 1, 3 ]

Fact(4) = [ 1, 2, 4 ]

Fact(5) = [ 1, 5 ]

Fact(6) = [ 1, 2, 3, 6 ]

Fact(7) = [ 1, 7 ]

Fact(8) = [ 1, 2, 4, 8 ]

Fact(9) = [ 1, 3, 9 ]

Fact(10) = [ 1, 2, 5, 10 ]

Fact(11) = [ 1, 11 ]

Fact(12) = [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12 ]

Fact(13) = [ 1, 13 ]

Fact(14) = [ 1, 2, 7, 14 ]

Fact(15) = [ 1, 3, 5, 15 ]

Fact(16) = [ 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 ]

Fact(17) = [ 1, 17 ]

Fact(18) = [ 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18 ]

------------------------------

1 5 7 11 13 17

Φ 18 = 6

From here, we can see that the numbers 1, 5, 7, 11, 13, and 17 do not share any factors with 18 (other than "1"). Since there are six of these numbers, Φ 18 = 6. As you can see, this is a very difficult problem to solve as it involves factoring a great deal of numbers, then comparing all of those factors for similarities.

But there is one class of numbers for which calculating Φ is easy - primes.

Φ 5 = ? Φ 7 = ?

------------------------------ ------------------------------

Fact(1) = [ ] Fact(1) = [ ]

Fact(2) = [ 1, 2 ] Fact(2) = [ 1, 2 ]

Fact(3) = [ 1, 3 ] Fact(3) = [ 1, 3 ]

Fact(4) = [ 1, 2, 4 ] Fact(4) = [ 1, 2, 4 ]

Fact(5) = [ 1, 5 ] Fact(5) = [ 1, 5 ]

Fact(6) = [ 1, 2, 3, 6 ]

Fact(7) = [ 1, 7 ]

------------------------------ ------------------------------

Φ 5 = 4 Φ 7 = 6

From this, we can easily see that "Φ n" = "n -1" if "n" is a prime number. Φ is difficult to compute for most numbers, but ridiculously simple for primes.

What's even more interesting is that Φ is multiplicative. This means that "Φ n" _ "Φ x" = "Φ (n_x)". Here's an example to illustrate this.

4 * 5 = 20

--------------------

Φ 4 = 2

Φ 5 = 4

Φ 20 = ?

------------------------------

Fact(1) = [ 1 ]

Fact(2) = [ 1, 2 ]

Fact(3) = [ 1, 3 ]

Fact(4) = [ 1, 2, 4 ]

Fact(5) = [ 1, 5 ]

Fact(6) = [ 1, 2, 3, 6 ]

Fact(7) = [ 1, 7 ]

Fact(8) = [ 1, 2, 4, 8 ]

Fact(9) = [ 1, 3, 9 ]

Fact(10) = [ 1, 2, 5, 10 ]

Fact(11) = [ 1, 11 ]

Fact(12) = [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12 ]

Fact(13) = [ 1, 13 ]

Fact(14) = [ 1, 2, 7, 14 ]

Fact(15) = [ 1, 3, 5, 15 ]

Fact(16) = [ 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 ]

Fact(17) = [ 1, 17 ]

Fact(18) = [ 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18 ]

Fact(19) = [ 1, 19 ]

Fact(20) = [ 1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 20 ]

------------------------------

Φ 20 = 8 # since 1, 3, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 19 do not share any factors with 20 Since finding Φ for any prime number is easy, if we know the prime factors of a number, finding Φ for that number is also easy. For instance, the prime factors of 90,943 are 199 and 457, so Φ 90,943 = 90,288.

Φ199 = 198

Φ457 = 456

Φ90,943 = Φ199 * Φ457

Φ90,943 = 90,288

RSA and Φ

When RSA keys are generated, we randomly select two very large prime numbers. We will call those "p" and "q" in our examples. These two primes are then multiplied to produce "N". Since both "p" and "q" are prime numbers, it's easy

for us to compute the value of "Φ N", but incredibly difficult for anyone who does not already know the factorization of "N".

N = p * q

Φp = p - 1

Φq = q - 1

ΦN = (p - 1) * (q -1)

This is one of the secrets of RSA. As long as we can be reasonably certain that no one else knows the factorization of "N", we can publish "N" as part of our public key and "Φ N" will be used as part of our decryption function.

Euler's theorem

The next bit of higher order math (which will twist your neurons into knots) is Euler's Theorem. This states that if we have two numbers which are coprime (we will call them "a" and "b"), then:

a**(Φb) = 1 mod b # If a and b are coprime

We should take a moment here to review the meaning of "coprime" as we've not discussed this yet. Numbers are coprime if they do not share any prime factors. Let's back up and look at our factoring table from earlier (I've removed all of the factors which are not prime numbers for clarity).

Fact(1) = [ ]

Fact(2) = [ 2 ]

Fact(3) = [ 3 ]

Fact(4) = [ 2 ]

Fact(5) = [ 5 ]

Fact(6) = [ 2, 3 ]

Fact(7) = [ 7 ]

Fact(8) = [ 2 ]

Fact(9) = [ 3 ]

Fact(10) = [ 2, 5 ]

Fact(11) = [ 11 ]

Fact(12) = [ 2, 3 ]

Fact(13) = [ 13 ]

Fact(14) = [ 1, 2, 7 ]

Fact(15) = [ 3, 5 ]

Fact(16) = [ 2 ]

Fact(17) = [ 17 ]

Fact(18) = [ 2, 3 ]

Fact(19) = [ 19 ]

Fact(20) = [ 2, 5 ]

This is a list of all the prime factors for any given integer between 1 and 20. Looking at this table, we can see that "8" and "15" are coprime because their respective prime factors ("[ 2 ]" and "[ 3, 5 ]") do not overlap.

Using Euler's Theorem, we can see that:

8**(Φ15) = 1 mod 15

--------------------

8**8 = 16,777,216

16777216 / 15 = 1,118,481.0666

15 *1,118,481 = 16,777,215

`

`

Now, to make use of Euler's Theorem, we must modify the equation slightly by using two simple rules. The first rule is that "1" raised to any power always equals "1".

`1**0 = 1

1**1 = 1

1**2 = 1

1**3 = 1

1**x = 1`

Since our equation always equals "1" (after the modular arithmetic is performed), we can raise it to any exponent. We'll call this exponent "k".

Updated 7 months ago